Quick-Start Guide to Managing Invasive Aquatic Vegetation (IAV) in Tidal Wetland Habitats of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and Suisun Marsh

DIISCT (Delta Interagency Invasive Species Coordination Team)

Contributors in alphabetical order:

- Elizabeth Brusati, Delta Stewardship Council

- Jeffrey Caudill, California Department of Parks and Recreation, Division of Boating and Waterways

- Gina Darin, California Department of Water Resources, Fish Restoration Program

- Daniel Ellis, Interagency Ecological Program

- Julie Gonzalez, San Francisco Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve

- Shruti Khanna, California Department of Fish and Wildlife and Interagency Ecological Program

- Nick Rasmussen, California Department of Water Resources

- Rachel Wigginton, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Conservancy

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this guide are those of the authors and do not represent official policy of any agency or organization. The IAV Guide is intended as a general resource and does not replace site-specific recommendations from a licensed Pest Control Advisor.

Introduction

Welcome to the “Quick-Start Guide for Managing Invasive Aquatic Vegetation in Tidal Wetland Habitats in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and Suisun Marsh” (guide). This guide is intended to give land managers an introduction to managing invasive aquatic vegetation (IAV) in tidal wetland habitats, whether the site is established, has been recently restored, or tidal reconnection will soon occur. It addresses submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), floating aquatic vegetation (FAV), and emergent aquatic vegetation (EAV) (see Definitions). It compiles knowledge from land managers in the Delta and members of the Delta Interagency Invasive Species Coordination Team (DIISCT), whose purpose is to foster communication and collaboration among California state agencies, federal agencies, research and conservation groups, and other interested parties that detect, prevent, and manage invasive species and restore invaded habitats in the Delta. The authors hope this guide functions like asking an experienced colleague for recommendations as you start to consider your site’s IAV management.

This guide is not a literature review or a synthesis of the research on IAV control. As you develop your invasive species management plans, please consider this guide a start and not an end to your planning. This guide summarizes information and refers readers to more detailed sources across the entire sequence of IAV management, from planning and prioritizing species, control and monitoring, and regulatory and budget considerations. While tidal wetland sites may also experience impacts from invasive upland or riparian plants, those species are outside the scope of this guide because the control methods and regulatory considerations differ from those of IAV.

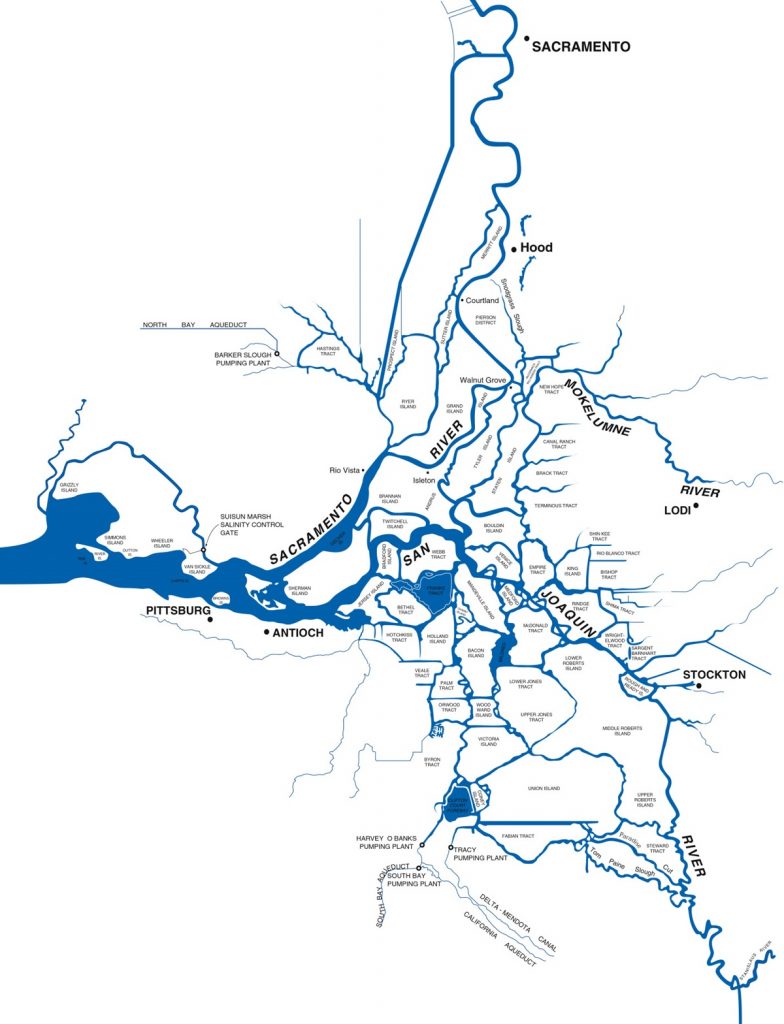

This guide focuses on the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta of California (Delta) and Suisun Marsh (Marsh) because of their unique geographical, ecological, and regulatory challenges. However, many of the resources in this guide provide information relevant to invasive plant management in other locations and habitats. Tidal wetland managers in the Delta and Marsh must consider seasonal water flows, tidal flows, many special-status species, and the need to balance project goals with the broader regulatory context. These considerations constrain the timing and methods used in IAV management.

If you have feedback or corrections to inform future versions of this guide, please submit them here.

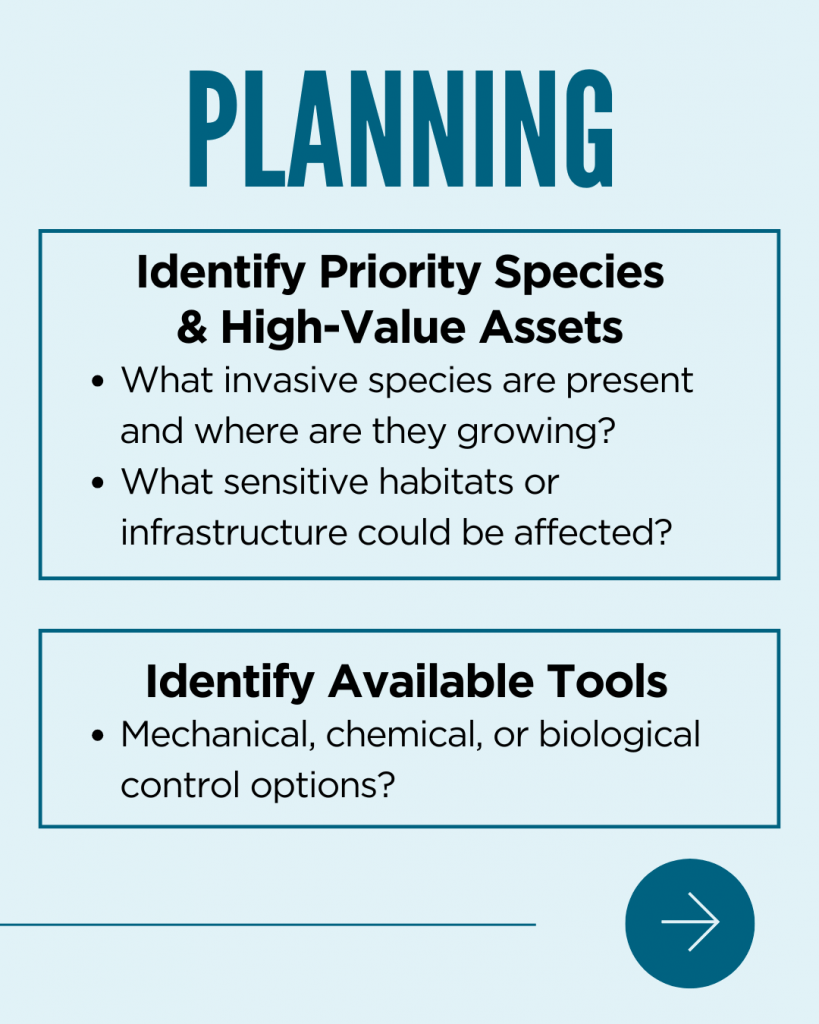

Determine Invasive Aquatic Vegetation (IAV) Management Goals and Objectives

Click to expand/collapse

Step 1. Think about your why

The reason(s) you want to manage IAV will help determine the most appropriate approach. Step back and think about why you are interested in managing IAV. What is the purpose of the project? Consider your management goal, such as habitat enhancement for a particular special status species, water conveyance, or recreational access. Brainstorm your “why” with your team.

Step 2. Develop Management Goals

Setting goals and objectives is important for many reasons:

- Goals ensure IAV management aligns with restoration priorities.

- Specific objectives will help you balance trade-offs such as short-term vegetation removal versus long-term ecological resilience. For example, invasive Himalayan blackberry, tamarisk, or phragmites are sometimes used by native species, but if the invasive species dominate the site there might be other ecological harms impacting those same native species.

- Management goals help facilitate adaptive management.

- Goals improve efficiency and resource allocation.

Work with your team to draft realistic goals and SMART objectives (i.e., specific, measurable, achievable, results-oriented, time-bound) for your site. Having SMART objectives promotes structured monitoring and subsequent adjustments based on management action outcomes, changing environmental conditions, regulatory updates, and emerging best practices. For example, herbicide application by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) is an emerging technique that may be appropriate at some sites but may not have been considered during initial management planning.

Understanding who is needed to achieve your objectives can promote useful collaborations among agencies, land managers, researchers, tribes, and local communities by ensuring everyone is working toward shared objectives. Such collaborations and demonstrated efficiencies may help secure funding and regulatory approvals.

Step 3. Define Success

Identify success criteria and a monitoring plan for each objective. Stated objectives should come with measurable success criteria, which act as benchmarks for evaluating the effectiveness of your IAV control efforts.

Additional Resources:

- Weed Management Areas are cooperative groups that can be valuable sources of local knowledge.

- Land Manager’s Guide to Developing an Invasive Plant Management Plan, (USFWS and Cal-IPC 2018) includes guidance on developing objectives, evaluating activities in relation to objectives, and creating monitoring plans. It also contains a sample plan template.

Identify the Invasive Aquatic Vegetation (IAV) Species in Tidal Wetlands of the Delta and Marsh

Click to expand/collapse

Several tools are available to help you determine which species occur at or near your site. CalFlora hosts a What Grows Here tool, which allows you to draw a polygon around your site area to produce a plant species list with images and invasive species status, among other species details. CalWeedMapper may also be a useful tool for developing your site’s species list. However, community science-based sites such as these can contain misidentifications, especially for species that are difficult to identify or hybridize, such as Ludwigia spp. and Phragmites (native vs non-native biotypes). For unknown species found at your site, CDFA’s Botany Laboratory provides plant identification services, as do some university or private laboratories.

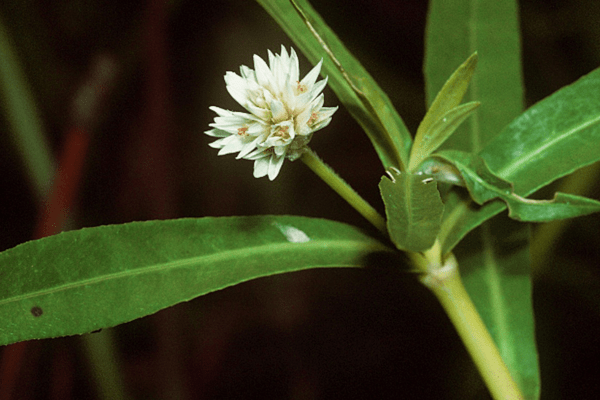

Table 1. A selection of invasive IAV species that are particularly prevalent or impactful in the Delta and Suisun Marsh. Consider these and other region-specific species when planning management actions. “Type” refers to the category of IAV – submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), floating aquatic vegetation (FAV), and emergent aquatic vegetation (EAV) – for each species. “DBW treatment list” refers to whether a species is on the State Parks Division of Boating and Waterways treatment list.

| Species (Common Name) | Type | DBW treatment list |

|---|---|---|

| Egeria densa (Brazilian waterweed) | SAV | Yes |

| Alternanthera philoxeroides (Alligatorweed) | FAV | Yes |

| Myriophyllum spicatum (Eurasian watermilfoil) | SAV | Yes |

| Potamogeton crispus (Curlyleaf pondweed) | SAV | Yes |

| Vallisneria australis (Ribbonweed) | SAV | Yes |

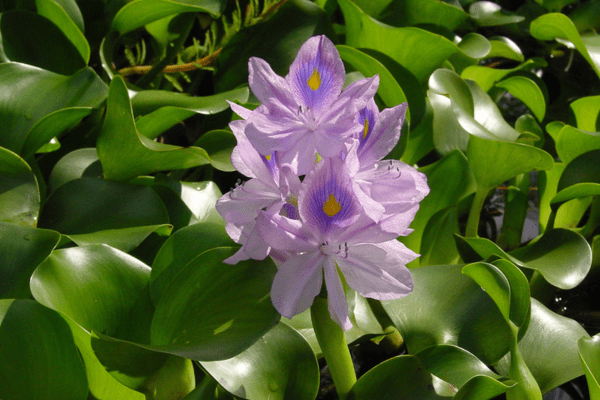

| Eichhornia crassipes (Water hyacinth) | FAV | Yes |

| Limnobium laevigatum (West Indian spongeplant) | FAV | Yes |

| Ludwigia spp. (Water primroses)* | FAV/EAV | Yes |

| Iris pseudacorus (Yellow flag iris) | EAV | No |

| Phragmites australis (Common reed) | EAV | No |

| Arundo donax (Giant reed) | Levee | No |

| Lepidium latifolium (Perennial pepperweed) | Levee | No |

Additional Resources:

- The Suisun Resource Conservation District has developed a useful, descriptive guide to native and non-native species commonly found in the Suisun Marsh.

- The species identification booklet for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta includes photos and plant identification characteristics.

- Weed Management Areas are cooperative groups that can be a valuable source of local knowledge.

- The University of California Weed Research and Information Center provides publications, training videos, a photo gallery, and other resources.

(Photo by National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA)

(Photo by Cardex)

(Photo by Wouter Hagens)

Prioritize Species and Sites

Click to expand/collapse

No entity working in the Delta has enough staff, resources, or funding to eradicate every invasive aquatic vegetation (IAV) target species. Managers must prioritize based on the project’s goals and objectives, but how can you best do this?

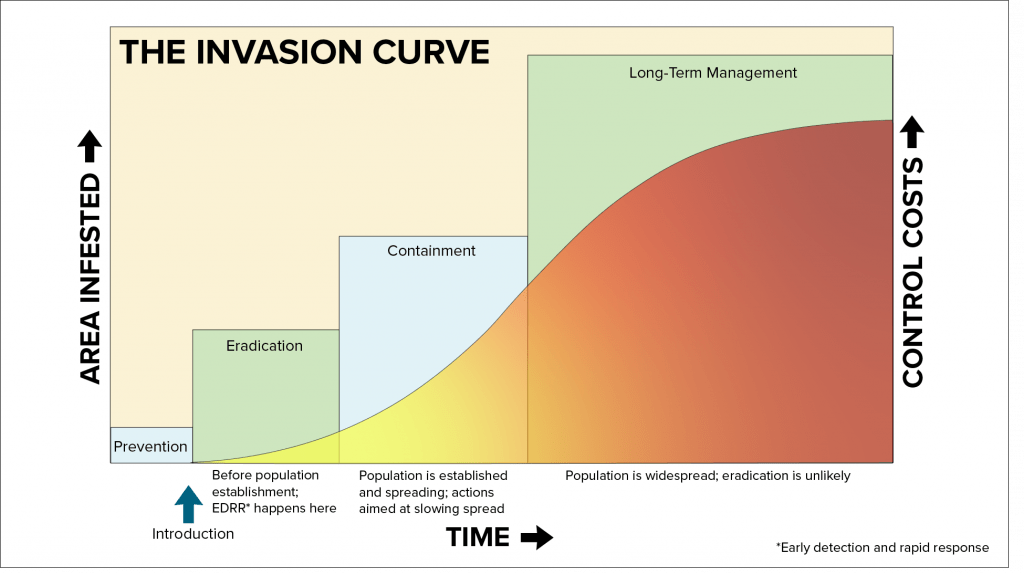

The Invasion Curve and Early Detection

The management strategies you choose should be tailored to the species’ invasion stage and available resources at your site. The invasion curve is a conceptual model illustrating the relationship between the extent of an invasive species’ spread and the time since the introduction of the invasives species. The invasion curve can also be used to conceptualize the effort required for management over time because once a species is established at a site it is likely to require long-term management.

Four key management actions are typically mapped onto the invasion curve (Interior 2016):

- Prevention: This occurs before introduction. During this phase management has the lowest cost and is most effective.

- Eradication: This occurs after the introduction of the invader but before it has begun to spread and cause harm. Management actions aiming to eradicate the invader have the highest potential for success during this phase. This is the phase during which early detection, rapid response actions occur.

- Containment: This occurs after the invasive species has established and begun to spread. Management actions during this phase are focused on slowing the spread of the species. Increased effort and cost are required to implement management actions during this phase.

- Long-Term Management: This occurs after the invasive species has spread across the site and eradication is deemed unlikely. Management costs are highest during this phase because control is ongoing and costs and effort compound over time.

Prevention takes place before the introduction of a new invasive species to your site. This process includes identifying pathways and vectors for movement and applying measures to control spread. This can be difficult when viewing prevention at the level of parcels or properties, rather than a watershed or landscape approach, because many of the IAV species are already widespread in the Delta and Marsh and spread through natural means is likely.

Early detection and rapid response (EDRR) is the coordinated set of actions that aim to find and report, then eradicate potential invasive species before they spread and cause harm (Interior, 2016). Limiting the establishment of new invasive species at your site requires less resources than long-term management. For this reason, prevention and EDRR should be prioritized as part of your site management plan.

Your ability to effectively respond to new invaders at your site will be strongly influenced by the location of your site and the invasion status of connected sites and systems. The DIISC Team has developed a draft EDRR plan and coordination table (available upon request) for the region based on the National EDRR Framework, but many of the same elements can apply at the site level. These elements include preparedness, early detection, rapid assessment, and rapid response.

A fast response to a new invader is not possible without the preparation of an action plan, which includes how you will communicate and coordinate with relevant actors and a way to quickly bring together resources for action. One of the key elements of being prepared is having a plan; Cal-IPC’s Land Manager’s Guide to Developing an Invasive Plant Management Plan is a useful reference. Another key aspect of preparedness is developing a list of species likely to invade your site. CalWeedMapper and CalFlora’s What Grows Here can be useful tools for this planning. If you have jurisdiction and ability, treating nearby sites could limit propagule pressure for your site and be an effective part of your broader plan.

Coordinated management and monitoring activities should ensure the early detection of the first occurrence of an invasive species is reported and the species identity is confirmed (Interior, 2016). Consider the scale and frequency of your monitoring and if they are sufficient to result in the early detection of species likely to invade the site. The timing and intensity of your monitoring should be informed by the site characteristics (e.g., size, geomorphology, hydrology) and the list of species likely to invade, but some unknowns remain about monitoring approaches to detect new invaders in the Delta (see Management Uncertainties). All monitoring staff should have training in identification of species likely to invade the site, and there should be a clear structure in place for monitoring staff to report potential new invaders.

You should plan a set of rapid assessments to determine the distribution and abundance of a new invasive species, evaluate its potential risk to the site, and identify control options (Interior, 2016). The Delta Interagency Ecological Program released a technical report entitled, “Framework for Aquatic Vegetation Monitoring” in 2018, which describes remote imagery, SAV Rake, and other sampling methods (IEP 2018). The report does not establish recommendations for sampling intensity or scale, and these should be developed based on your site characteristics (e.g., size, geomorphology, hydrology). Cal-IPC describes weed risk assessments and provides useful links on their website. Have a plan for how you will determine the acceptable level of risk for your site, and have a structure to communicate the risk to your team members and collaborators. See Choose Control Methods.

Finally, rapid response helps coordinate actions to eradicate a new potentially invasive species before it becomes established and eradication is no longer likely (Interior, 2016; Reaser, et al., 2020). Containment and quarantine need to happen quickly for effective eradication, and relevant actors need to be empowered by leadership to move quickly before eradication is impossible. Quick actions in the moment require you to think ahead as described above and fold potential new invaders into your permitting and control choices.

Prioritization Tools

Depending on the stage of the invasion curve, your project goals and objectives, and your available resources (e.g., staff, equipment, money, permits), you’ll need to prioritize your efforts to certain species, specific populations of that species, and/or high-value areas within your project. WHIPPET (Weed Heuristics: Invasive Population Prioritization for Eradication Tool) is an online decision-support tool that helps land managers prioritize invasive plant populations for eradication based on factors like impact, feasibility, and spread risk.

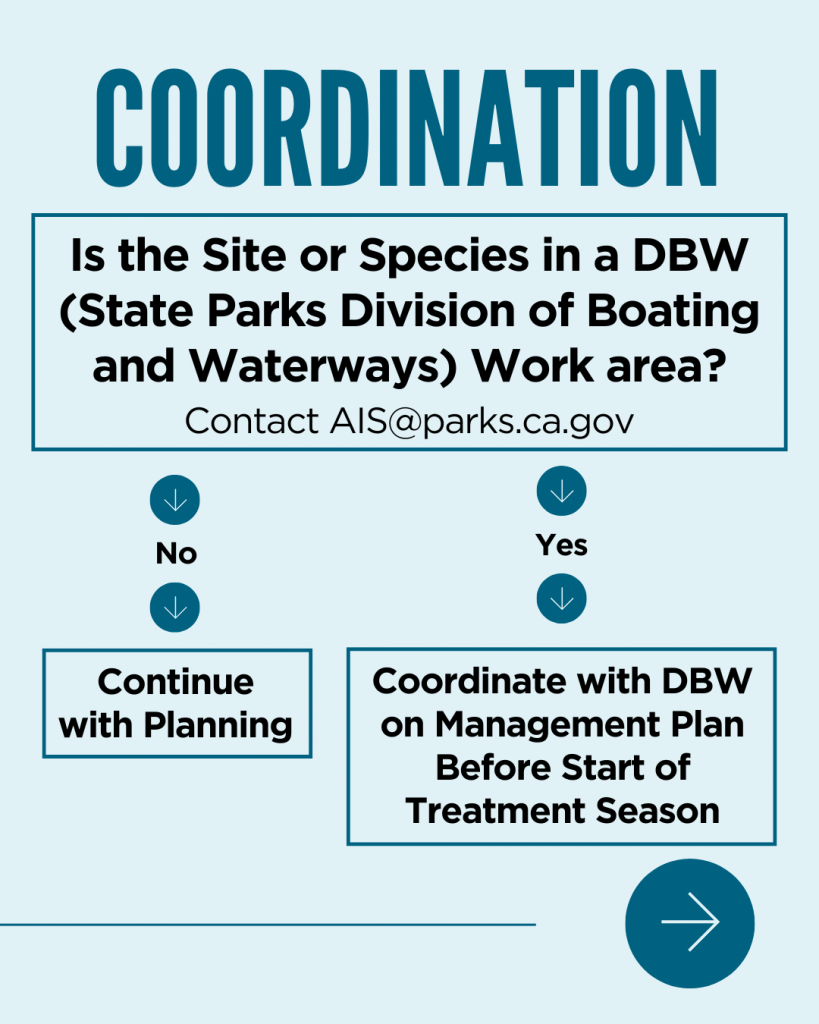

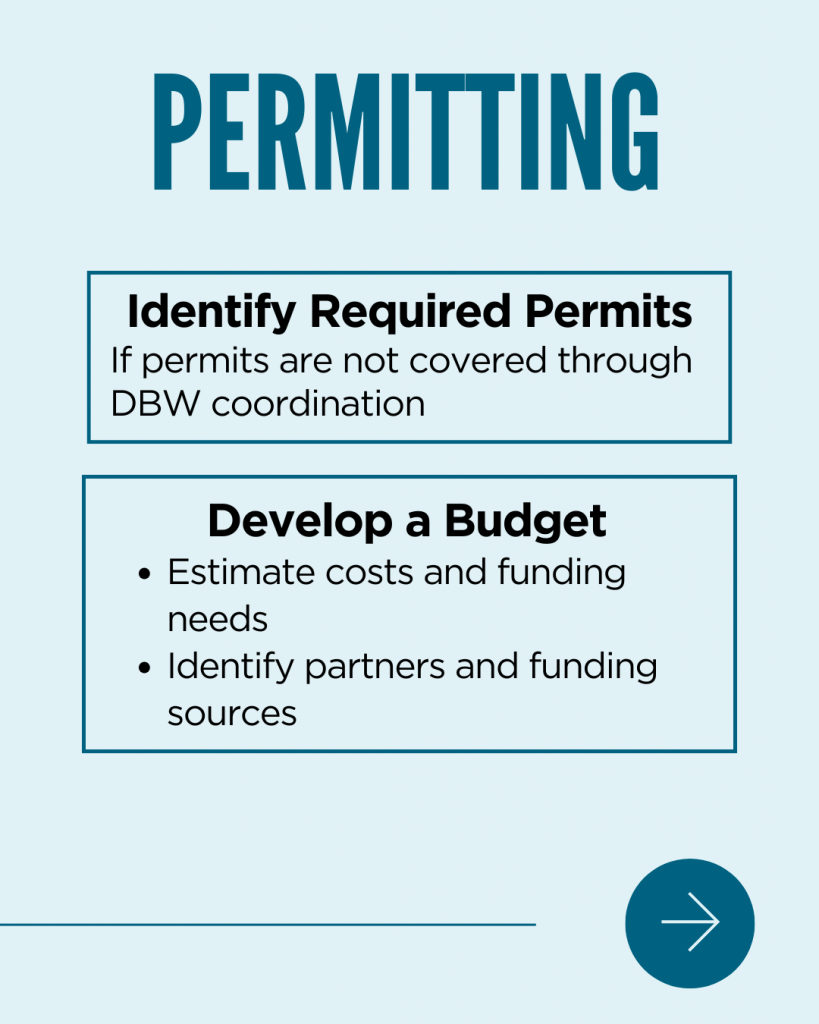

Plan for Permitting and Environmental Compliance

Click to expand/collapse

Depending on the size and location of your site and the control methods you choose, different permits may be required. Each permit has an associated cost and required amount of lead time for approval. This guide provides an overview of many commonly required permits. However, it is the responsibility of each project proponent to ensure all needed permits and environmental compliance actions are complete.

The Accelerating Restoration website provides summaries of project permitting needs, exemptions for habitat restoration projects, and the eligibility requirements for exemptions. It includes a list of permitting pathways by agency and a Protection Measures Selection Tool. Sustainable Conservation’s Essential Guide for Accelerated Restoration Permitting summarizes state and federal options for accelerated permitting. California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (CDFW) Cutting the Green Tape webpage has additional information about the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) statutory exemption for restoration projects (SERP) and other streamlined permitting tools. All price estimates shown in this section are based on costs in Fiscal Year 2024/2025.

Pest Control Advisors

In California, a Pest Control Advisor (PCA) is a licensed professional who provides recommendations on the use of pest control products. It is highly recommended that you have a PCA visit your site annually and prepare a written prescription. This will cost roughly $3,000 if you don’t have a PCA in house. This price includes a fee of $400 per recommendation, consulting time, and travel expenses for site visits (e.g., boat-in) on contract.

Endangered Species Considerations

The Delta contains many special status species and their critical habitat; thus, your permitting plan will likely need to consider both the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) and California Endangered Species Act (CESA). Be aware of the potential for listed species in your project area. One way to check for potential endangered species presence is through the California Natural Diversity Database CNDDB/BIOS. Determining what species are present may also be done through pre-treatment monitoring plans. If your chosen control method(s) are likely to have take of endangered species, then you will need to apply for ESA/CESA take coverage. Take is any activity that harasses, harms, kills, traps, or collects a state or federally listed endangered species. Incidental take permits for the ESA and CESA are issued to allow permittees to take listed species as long as the take is not the purpose of the permitted activity (i.e., incidental to the permitted actions). We recommend doing everything in your power to choose control methods that avoid take. A CESA Incidental Take Permit (ITP) costs $25,000.

CEQA and NEPA

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) requires government agencies to consider the environmental consequences of their actions before approving action on a project (Public Resources Code 21000–21189). If your project is eligible for a CEQA exemption, this can save both time and money. Otherwise, the CEQA lead agency will need to perform analysis (e.g., Initial Study and Mitigated Negative Declaration) and potentially make findings. An invasive aquatic vegetation (IAV) management project alone is unlikely to require a full Environmental Impact Report under CEQA, but IAV management may be only a portion of a larger project (e.g., tidal wetland restoration) that could need more extensive CEQA evaluation.

CEQA exemptions that may be relevant include:

- Categorical exemption for small restoration projects (less than 5 acres, Title 14, Section 15333),

- Categorical exemption for minor alterations of land (Title 14, Section 15304),

- Statutory exemption for restoration projects (SERP, Public Resources Code Section 21080.56).

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) may apply and require consultation with federal agencies. NEPA coverage may be needed for an invasive aquatic vegetation control project when the project involves federal funding, requires a federal permit, occurs on federal land, or may significantly impact the environment. In such cases, a federal agency must evaluate the potential environmental effects of the project through a categorical exclusion, Environmental Assessment (EA), or Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), depending on the scope and scale of the project.

Clean Water Act

If you plan to spray herbicides over water with a continuous surface connection to Waters of the United States, then compliance with Clean Water Act (CWA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) is required. In California, NPDES is administered by the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB). There is a National General Permit for aquatic weed control. This permit is expired, but it stands until a new one is posted. The process to be covered under this permit is to submit a Notice of Intent (NOI) for an Aquatic Pesticide Application Plan (APAP). Examples are posted on the website. Annual fees can vary, but you should expect to pay $3,000 per year in permit fees. This also requires you to perform water quality compliance monitoring. Samples cost approximately $300 per sample to analyze. You need a pre-, during, and post-event sample for every analyte on each spray day. It is best to plan your spraying at one site to occur all at one time to minimize water quality sample analysis costs. After six consecutive results below threshold, no more sampling is required at that site for that analyte for that activity in that year. Glyphosate and nonylphenols have some special rules, so read your permit carefully.

If the project involves placing materials (e.g., herbicides, sediment, or structures) into waters of the United States or affecting navigable waterways, consultation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is typically required under Section 404 of the Clean Water Act and Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act. In the Delta, the process begins with submitting a permit application to the USACE Sacramento District, including a project description, location map, and details on methods and potential environmental impacts. USACE reviews the application for compliance with environmental laws and may coordinate with other agencies, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) or the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) Fisheries, under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, and the State Historic Preservation Officer under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. The process may also involve public notice and comment if the project has broader implications. Timelines vary depending on project complexity and consultation requirements.

Lake and Streambed Alteration Agreement

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) requires a Lake or Streambed Alteration (LSA) Agreement when a project activity may substantially adversely affect fish and wildlife resources in a river, stream, or lake. Notify CDFW prior to conducting any activity that may impact natural flow; change the bed, channel, or bank; use material from a river, stream, or lake; or deposit material into a river, stream, or lake. You can notify CDFW using CDFW’s Environmental Permit Information Management System (EPIMS).

Choose Control Methods

Click to expand/collapse

The primary goal of controlling invasive aquatic vegetation (IAV) when eradication is not possible is to ensure the IAV are maintained at a level that does not unfavorably impact the environment, public health, or economy of the area. With many different control tools available, Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is an ideal approach, if resources allow, to form your long-term control strategy.

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is an ecosystem-based strategy focusing on long-term prevention of pests or their damage through a combination of techniques such as biological control, habitat manipulation, and modification of cultural practices. Pesticides are used after monitoring indicates they are needed and according to established guidelines, and treatments are made with the goal of removing only the target organism. Pest control materials are selected and applied in a manner that minimizes risks to human health, beneficial and nontarget organisms, and the environment. (UC IPM 2025)

The dynamic conditions in the Delta pose unique challenges for invasive aquatic vegetation (IAV) management. Tidal and seasonal flows can rapidly redistribute plant fragments and propagules, making containment and treatment more difficult. The presence of numerous special-status species requires careful planning to avoid unintended impacts from control actions, such as herbicide application or mechanical removal. Additionally, management strategies must align with a complex regulatory landscape, where permitting, timing, and coordination with multiple agencies are critical to ensure both ecological protection and project success. Hussner et al. (2017) and Conrad et al. (2023) summarize control methods and challenges for IAV.

It is critical to remember that management actions could result in movement of invasive species through the hydrologically interconnected system of the San Francisco Estuary. Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) Planning can be a tool to address this risk. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has developed an HACCP Manual.

IAV control tools include (DiTomaso et al. 2013):

- Chemical Controls (Aquatic Herbicides)

- Contact Herbicides

- Systemic Herbicides

- Tank Mixes

- Mechanical Control or Physical Removal

- Manual Removal

- Mowing or Cutting

- Heavy Equipment (i.e., Mechanical Harvesting)

- Biological Control

- Cultural Controls

- Grazing

- Prescribed Burning

- Competition

- Water Management

Chemical controls (aquatic herbicides) are generally the most cost-effective approach to controlling IAV in the Delta and Suisun Marsh (State Parks Division of Boating and Waterways (DBW), personal communication). For example, DBW has found the cost of treating 100 acres of invasive aquatic plants with herbicides is similar in cost to treating 1 acre by harvesting (see below). Herbicides have different modes of action and can be systemic or contact. The different modes of actions and types of herbicides are evaluated based upon environmental factors and the target IAV to determine the best tool for the target IAV. Always consult a Pest Control Advisor (PCA) when planning a chemical application and follow the pesticide label. Aquatic Pesticide Application Plans (APAPs) posted on the State Water Resources Control Board website provide examples.

In the Delta system, key challenges to using herbicides, particularly those targeting submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), are the strong water flows that can rapidly dilute chemicals below effective concentrations and turbidity that can reduce chemical efficacy if chemicals bind to suspended particles before IAV control can occur.

Mechanical control (or physical removal) generally uses mechanical harvesting or construction equipment (bulldozers or backhoes) to remove IAV from an area for spoiling or transport away from the site (Hussner et al. 2017). Other mechanical control techniques include string trimming, mowing, cutting, lopping, chain sawing, shredding, and vacuuming. Mechanical harvesting is generally a very resource-intensive option for managing IAV due to the amount of equipment and trained personnel required for the process to be successful, but it also has high efficacy if planned correctly. Mechanical harvesting FAV has been somewhat successful in the Delta (State Parks Division of Boating and Waterways, personal communication). You may face additional challenges when harvesting SAV due to the costly, resource-intensive approaches available and the fact that fragments can settle and recolonize the site or create a new population if fragments are transported downstream (Conrad et al. 2023). Mechanical harvesting may also result in bycatch (Ta et al. 2017).

Physical controls can be very useful depending on the target IAV species and project goals. Physical controls can include benthic mats, booms, and more. These tools are generally combined with another control tool, such as herbicides, to increase the efficacy of the overall treatment. For example, you could pair booms with mechanical harvesting for floating aquatic vegetation (FAV); the booms can help block fragments not being caught by harvesting before they flow downstream and potentially create new infestations.

Manual removal, which refers to removal with small hand tools, is another option for controlling smaller areas of IAV. Manual removal acts like a very small mechanical harvesting operation (Hussner et al. 2017). This approach requires a lot of physical labor, which makes it inefficient for more extensive invasions. Like mechanical removal, manual removal can create fragments that can cause infestations downstream (Conrad et al. 2023). For manual removal of SAV, consider both the potential to create plant fragments and the need for specialized training and equipment, depending on the depth of the area.

Biological Control (biocontrol) is the use of natural enemies such as predators, parasites, pathogens, and competitors to control pests and their damage (UC IPM 2025). It can be an effective, long-term control tool for managing IAV without the longer-term cost. Biocontrol agents do not need to be upkept after a successful establishment. However, biocontrol agents are not generally going to eradicate IAV. Instead, they control populations by reducing growth and spread, which can reduce chances of new infestations occurring near the site. Challenges to this approach include the significant upfront cost and testing required to bring in such agents. For example, some weevils and planthoppers used for controlling water hyacinth were found to not be as robust as water hyacinth and do not survive the winters very well, greatly reducing their ability to control water hyacinth (Hopper et. al. 2017, Hopper et. al. 2021). Few biocontrol options are available for SAV. Ta et al. (2017) summarizes biocontrol agents for Delta aquatic weeds. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, may be a source for advice and biocontrol agents.

Cultural control strategies use specific techniques to manipulate the environment to improve the growing conditions for desirable species while reducing weed populations (DiTomaso et al. 2013). These methods include targeted grazing by livestock to reduce biomass and suppress regrowth in uplands, as well as active revegetation with competitive, regionally appropriate native species that may outcompete invasive plants over time by occupying the same ecological niche. In some settings, cultural and controlled burning is also used strategically to remove accumulated thatch, which can stimulate native seed banks, reduce the competitive advantage of invasives, and improve access for follow-up treatments. If the restoration site is still a managed wetland, managing water levels can drown out or dry out IAV. When implemented thoughtfully and in coordination with mechanical and chemical methods, these cultural controls enhance long-term ecosystem resilience and support the recovery of native tidal wetland plant communities.

Regardless of the control method(s) you choose, monitor the treatment site during and after application. Post treatment monitoring should continue for at least three years to ensure IAV does not reestablish. Khanna et al. 2018 describes a range of methods for monitoring based on available budget.

Additional Resources:

- Weed Control User Tool (WeedCUT) is a decision-support tool from Cal-IPC and UC IPM that provides guidance on a range of methods for managing invasive plants in wildlands and helps practitioners select those that are most effective for different situations.

- The Suisun Resource Conservation District’s “Suisun Marsh Vegetation Guidebook” recommends control methods by species.

- Delta Region Areawide Aquatic Weed Project (DRAAWP) describes IAV control techniques and contains links to species-specific control information (at bottom of Aquatic Weeds page) and a special issue of the Journal of Aquatic Plant Management focused on the Delta.

Table 2. Selected control methods for IAV in the Delta.

| Species (Common Name) | Chemical | Mechanical | Biological | Cultural* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egeria densa (Brazilian waterweed) | x | |||

| Alternanthera philoxeroides (Alligatorweed) | x | |||

| Myriophyllum spicatum (Eurasian watermilfoil) | x | x | ||

| Potamogeton crispus (Curlyleaf pondweed) | x | |||

| Vallisneria australis (Ribbonweed) | x | |||

| Eichhornia crassipes (Water hyacinth) | x | x | x | x |

| Limnobium laevigatum (West Indian spongeplant) | x | |||

| Ludwigia spp. (Water primroses) | x | x | ||

| Iris pseudacorus (Yellow flag iris) | x | x | ||

| Phragmites australis (Common reed) | x | x | x | |

| Arundo donax (Giant reed) | x | x | x | x |

| Lepidium latifolium (Perennial pepperweed) | x |

Plan Your Budget

Click to expand/collapse

This section of the guide, Plan Your Budget, was created with the assistance of AI, which helped create a bulleted outline for the section. The content has been edited by Rachel Wigginton and reviewed by the co-authors of this guide. The authors take full responsibility for the final content.

Budget planning for an invasive aquatic vegetation (IAV) management project in the Delta or Suisun Marsh involves many factors, given the Delta’s unique ecological, regulatory, and hydrologic complexity. We have listed key factors to consider when building your budget and an example budget table that shows relative costs of the different potential budget categories (Table 3 and Table 4).

First, consider the project’s scope and scale. You will need to consider the total area that needs to be managed, the extent of the infestation, and the accessibility of the site. The target species should also be considered in your budget, since different species require different control methods and levels of effort. The duration of the treatment (e.g., annual, one season) will also affect the budget and will be informed by the previous considerations.

Monitoring and assessment costs will include pre-treatment surveys to establish baseline maps and understand the extent of the infestation and post-treatment monitoring to evaluate effectiveness and adjust the methods being used. Monitoring should also be sufficient to inform adaptive management at the site. Technology such as satellite imagery, drones, GPS mapping, and remote sensing may be needed. Any additional sampling needed to track unintended impacts of the project should be considered in the budget.

Next, you will need to budget for the equipment and supplies needed for your management actions. When choosing chemical controls, consider costs of herbicide, application equipment, licensing, safety gear, and safety training. For physical/mechanical removal, larger equipment like boats and harvesters may be needed. Manual control may require smaller hand tools. If you use biological control, you will need to pay the cost of sourcing and releasing biocontrol agents and monitoring effectiveness. Costs of cultural control vary based on the practice chosen; for example, grazing costs could include things like grazing leases.

No matter what approach you chose, permitting and regulatory compliance must be considered in the project budget. Some examples of permit costs include preparing CEQA/NEPA documentation, water quality permits, annual fees and water quality compliance monitoring, and various permit fees. Implementing best management practices to aid in environmental compliance should be considered in the budget. For example, best management practices for avoidance and minimization include time-of-year restrictions, buffers for sensitive species, and erosion control.

Outreach costs should also be considered. You may need to post public notices if work affects boating, recreation, or local communities. Tribal consultation should also be carried out when culturally sensitive areas are nearby or within the treatment area. Consider the costs of any other community education goals the project may support.

Labor and staffing must be budgeted to support all the activities described in the previous paragraphs. This includes time for hiring, training, and supervising staff. You may need field crews to perform management actions, specialists to provide scientific support (e.g., biologists, ecologists, restoration scientists) and project managers. Project management costs can include grant administration, reporting to funders and regulators, data management, and producing products, such as peer reviewed publications.

A contingency and adaptive management fund will allow you to adjust to unforeseen costs, such as weather delays, equipment failures, regulatory changes, new infestations, or new listings of endangered species. These funds also allow you the flexibility to adapt your methods if the initial approach proves ineffective.

Long-term maintenance and follow-up should also be considered in the overall funding of your control program. You will need to monitor for reinfestation, apply follow-up treatments as needed, and continue to incorporate weed management into your ongoing site stewardship.

Finally, if applicable, you will need to account for your organization’s indirect costs rate.

Consider Funding Opportunities

The federal government and State of California maintain grant portals that allow potential applicants to search for funding opportunities across multiple agencies. The California State Grants Portal allows you to search by applicant type (e.g., government, nonprofit, etc.) and sector (e.g., environment, parks and recreation, etc.). The State Grants Portal also offers an option to subscribe to grant opportunity updates. The passage of Proposition 4 in 2024 may provide funding to state agencies for new grant opportunities. Subscribing to the State Grants Portal updates will allow you to hear about these programs. Search the federal Grants.gov portal for funding opportunities from federal agencies.

California state agencies with relevant funding programs include:

- Department of Fish and Wildlife

- Department of Food and Agriculture Weed Management Area Grant Program

- Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Conservancy

- Wildlife Conservation Board

Other funders and funding databases include:

- National Fish and Wildlife Foundation

- National Wildlife Federation Nature-Based Solutions Funding Database

- San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority

The sample budget template below (Table 3) includes relative costs ($-$$$$) for an invasive aquatic vegetation management project in the Delta. This is designed to be flexible – you can modify line items depending on project size, duration, and funding source.

Table 3.

| Category | Line Item | Estimated Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Planning & Permitting | Pre-project planning meetings & coordination | $$ |

| California Environmental Quality Act/National Environmental Policy Act documentation (if required) | $$$$ | |

| Water quality permits (e.g., National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) | $$ | |

| Pesticide Use Permits & Reporting | $$ | |

| Environmental compliance (e.g., Endangered Species Act, cultural resources, etc.) | $$$$ | |

| Regulatory consultations (e.g., California Department of Fish and Wildlife, United States Fish and Wildlife Services, etc.) | $$ – $$$ | |

| Site-specific mapping & baseline surveys | $$ | |

| Monitoring & Data Collection | Pre-treatment vegetation surveys | $$ |

| Water quality monitoring (before/during/after) | $ | |

| Post-treatment effectiveness monitoring | $$ | |

| Data management (GIS mapping, data entry) | $ | |

| Control Methods | Herbicide purchase & delivery | $ – $$$$ |

| Application equipment (booms, spray boats) | $$ – $$$$ | |

| Mechanical harvesting (equipment rental or purchase) | $$$$ | |

| Biological control implementation (if used) | $ | |

| Fuel & equipment maintenance | $ | |

| Disposal of removed vegetation (haul off or composting) | $$ | |

| In-field adaptive management adjustments | $ | |

| Labor | Field crew salaries & benefits | $$ |

| Project manager/coordinator | $$ | |

| Scientific advisors/technical experts | $$ | |

| Safety training (herbicide application, equipment handling) | $ | |

| Permitting & reporting staff | $$ | |

| Public Outreach & Coordination | Community notifications (press releases, signage) | $ |

| Community meetings (agencies, tribes, landowners) | $ | |

| Boater & public education materials | $ | |

| Environmental BMPs | Time-of-year restrictions compliance | $ |

| Habitat protection buffers (native vegetation, fish habitat) | $ | |

| Spill response materials (herbicide work) | $ | |

| Erosion control (if needed for mechanical work) | $$$ | |

| Reporting & Documentation | Progress reports to funders | $ |

| Final project report | $ | |

| Photo documentation | $ | |

| Data submittal to statewide tracking databases | $ | |

| Indirect/Overhead | Administrative support (invoicing, grant reporting) | $ |

| Equipment storage (if long-term project) | $ | |

| Office supplies, software (GIS licenses, field tablets) | $ | |

| Contingency Fund | Weather delays, regulatory changes, new infestations | $-$$$ |

| Additional monitoring if unexpected conditions occur | $ |

While every project is unique in its budget, the table below (Table 4) shows the relative costs for each broad budget category.

Table 4.

| Category | Relative Cost |

|---|---|

| Planning & Permitting | $$$ – $$$$ |

| Monitoring & Data Collection | $ |

| Control Methods | $$$ |

| Labor | $$ |

| Public Outreach & Coordination | $ |

| Environmental BMPs | $ |

| Reporting & Documentation | $ |

| Indirect/Overhead | $ |

| Contingency Fund | $$ |

Management Uncertainties and Research Needs

Click to expand/collapse

Managers require tools to control invasive aquatic vegetation (IAV), which can block waterways, occupy habitat used by native fauna, and harbor predators of listed fishes – for example, in remnant and restored wetlands (Conrad et al. 2016, Johnston et al. 2018). A variety of treatments have been tested in the Delta, both to preclude the invasion of IAV, and to remove it once it has become established (Khanna et al. 2018). Despite this, the current toolkit for managers has had limited success and there is a need to develop and evaluate new tools for SAV control (Conrad et al. 2020). This section reviews some areas of uncertainty regarding IAV management in the Delta and Suisun Marsh and indicates some directions for future research.

There is remaining uncertainty about the nontarget effects of permitted herbicides. Herbicides may affect the benthic community as well as phytoplankton in the open water (Underwood et al. 1999, Conrad et al. 2020, Conrad et al. 2023). Additional study is needed to understand impacts of different tools in application. This includes developing a better understanding of how herbicides spread regionally after application (Conrad et al. 2020). Further study is also warranted to determine the potential toxicity of the herbicides in situ compared to the laboratory studies.

Existing tools for controlling IAV are limited (Conrad et al. 2023). Research is needed to develop novel methods such as physical controls, biological controls, and chemical herbicides. Information is needed on biological control agents that are better matched to the Delta’s climate than those currently available (Conrad et al. 2023). Physical controls include barriers as well as creative restoration designs. Bubble curtains and benthic mats are experimental methods and their efficacy in the Delta is still under investigation. Bubble curtains may increase residence time of the herbicides applied to SAV, which could increase herbicide efficacy by increasing contact time while reducing the herbicide loading in the area (Conrad et al. 2020). When the submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) area is small, herbicides can be applied under a benthic mat to increase efficacy (Conrad et al. 2020). Modeling studies examining how restoration design elements could help exclude IAV would also be valuable.

Knowing the extent of current invasions and the potential for expansion of invasive populations is a key uncertainty in the Delta and Suisun Marsh. The Delta Stewardship Council (2022) reported a need to, “Enhance monitoring and model interoperability, integration, and forecasting for aquatic vegetation, SAV in particular.” Additionally, while emergent aquatic vegetation (EAV) and floating aquatic vegetation (FAV) can be adequately mapped using remote imagery, SAV is more challenging, and speciation of SAV is not yet possible. Environmental DNA (eDNA) tools may prove useful in the future but have not yet been implemented in the Delta.

Less is known about the ecological role of invasive vegetation in Delta wetlands than in other parts of the estuary. Restoration managers need information on effects of vegetation removal in Delta wetlands and the potential food web impacts. For new restorations, pre-planting methods could be tested to determine the best approach to keeping out IAV.

Research backed recommendation about how often and to what extent monitoring needs to happen pre, during, and post treatment are needed in the region.

Definitions

Click to expand/collapse

Adaptive Management – A framework and flexible decision-making process for ongoing knowledge acquisition, monitoring, and evaluation leading to continuous improvements in management planning and implementation of a project to achieve specified objectives (CA Water Code Section 85052).

Biological Control – The use of natural enemies – predators, parasites, pathogens, and competitors – to control pests and their damage (UC IPM 2025).

Chemical Control – The use of pesticides. In IPM (below), pesticides are used only when needed and in combination with other approaches for more effective, long-term control. Pesticides are selected and applied in a way that minimizes their possible harm to people, nontarget organisms, and the environment (UC IPM 2025).

Delta – The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and Suisun Marsh of California.

Early Detection – Coordinated monitoring activities to ensure the initial occurrence of a potentially invasive species is expeditiously reported, and the species identify is verified (Interior, 2016).

Early Detection and Rapid Response (EDRR) – A coordinated set of actions that aim to find and report, then eradicate potential invasive species before they spread and cause harm (Interior, 2016).

Emergent Aquatic Vegetation (EAV) – Macrophytes rooted in sediments with the majority of their stems, leaves, and flowers extending partially or fully out of the water. They are reeds and sedges generally erectophile in leaf structure and rely on the substrate for nutrients and anchorage (Mudge 2018). They grow in the intertidal zone of the estuary.

Floating Aquatic Vegetation (FAV) – Macrophytes that grow on the water surface with most of their stems, shoots, leaves, and flowers out of the water. They obtain nutrients directly from the water column through roots located at or below the water and do not require substrate for survival (Mudge 2018). For the purposes of this guide, we consider species like Ludwigia as floating because although they anchor in the substrate, they send out runners over the water surface with adventitious roots that derive nutrients directly from the water column.

Incidental Take Permit (ITP) – “Allows a permittee to take a CESA-listed species if such taking is incidental to, and not the purpose of, carrying out an otherwise lawful activity. […] Permittees must implement species-specific minimization and avoidance measures, and fully mitigate the impacts of the project.” (CDFW website, Fish and Game Code Section 2081 (b); Cal. Code Regs., tit. 14, sections 783.2-783.8).

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) – An ecosystem-based strategy focusing on long-term prevention of pests or their damage through a combination of techniques such as biological control, habitat manipulation, and modification of cultural practices. Pesticides are used after monitoring indicates they are needed according to established guidelines, and treatments are made with the goal of removing only the target organism. Pest control materials are selected and applied in a manner that minimizes risks to human health, beneficial and nontarget organisms, and the environment. (UC IPM 2025).

The Invasion Curve – A conceptual model illustrating the relationship between the extent of an invasive species’ spread and the time since the introduction of the invasive species.

Invasive Aquatic Vegetation (IAV) – Plant species that establish and spread in water-dominated environments, interfering with the intended land management goals and ecological functions of a site. These species can disrupt water flow, degrade habitat quality, hinder restoration efforts, and complicate resource management by outcompeting desirable vegetation, altering hydrology, or increasing maintenance costs. May include native or non-native species.

Manual Control – Mechanical and physical controls kill a pest directly, block pests out, or make the environment unsuitable for it (UC IPM 2025).

Pest Control Advisor (PCA) – A licensed professional who provides written recommendations on the use of pesticides. They are responsible for ensuring that these recommendations are safe for the environment, workers, and consumers, and that they are effective in controlling pests. PCAs must adhere to strict regulations set by the California Department of Pesticide Regulation (CDPR).

Preparedness – Preparedness activities establish plans, map coordination and communication networks, and develop tools, training, and resources necessary for EDRR actions (Interior, 2016).

Rapid Assessment – A set of actions to determine the distribution and abundance of the species, evaluate its potential risk to the site, and identify options for rapid response (Interior, 2016).

Rapid Response – Coordinated actions to eradicate a new potentially invasive species before it becomes established and eradication is no longer feasible (Interior 2016, Reaser, et al., 2020).

Submersed Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) – Macrophytes that are often rooted in sediments, with the majority of the plant body at or below the water surface (Mudge 2018). In the Delta, they grow in the subtidal to intertidal region of the estuary.

Take – To harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct (Endangered Species Act, 1973).

References Cited

Click to expand/collapse

Carruthers R, Anderson LWJ, Becerra L, Ely T, Malcolm J, Newman G, Yelle K, Llaban A, Ryan P, California Dept of Boating and Waterways. 2012. Water hyacinth control program: A program for effective control of water hyacinth in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta and its tributaries (Biological Assessment). Sacramento (CA): United States Department of Agriculture, California Department of Boating and Waterways.

Christman M, Khanna S, Drexler J, Young M. 2022. Ecology and ecosystem impacts of submerged and floating aquatic vegetation in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science 20(3). https://doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2022v20iss3art3

Conrad JL, Bibian AJ, Weinersmith KL, De Carion D, Young MJ, Crain P, Hestir EL, Santos MJ, Sih A. 2016. Novel species interactions in a highly modified estuary: association of largemouth bass with Brazilian waterweed Egeria densa. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 145:249–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/00028487.2015.1114521

Conrad JL, Chapple D, Bush E, Hard E, Caudill J, Madsen JD, Pratt W, et al. 2020. Critical needs for control of invasive aquatic vegetation in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. Sacramento (CA): Delta Stewardship Council. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351250055

Conrad, J. L; Thomas, M.; Jetter, K.; Madsen, J.; Pratt, P.; Moran, P., et al. (2023). Invasive Aquatic Vegetation in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta and Suisun Marsh: The History and Science of Control Efforts and Recommendations for the Path Forward. San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 20(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2023v20iss4art4 Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2v20x6zp

Delta Interagency Ecological Program. 2018. Framework for Aquatic Vegetation Monitoring in the Delta. https://cadwr.app.box.com/v/InteragencyEcologicalProgram/file/571038144141

Delta Stewardship Council, Delta Science Program. 2022. 2022–2026 science action agenda. https://scienceactionagenda.deltacouncil.ca.gov/pdf/2022-2026-science-action-agenda.pdf. Accessed 2025 Mar 17.

DiTomaso, JM; Kyser, GB; Oneto, SR; Wilson, RG; Orloff, SB; Anderson, LW; Wright, SD; Roncoroni, JA; Miller, TL; Prather, TS; Ransom, C; Beck, KG; Duncan, C; Wilson, KA; & Mann, JJ. (2013). Weed Control in Natural Areas in the Western United States. University of California Weed Research & Information Center.

Hopper, J. V., Pratt, P. D., McCue, K. F., Pitcairn, M. J., Moran, P. J., & Madsen, J. D. (2017). Spatial and temporal variation of biological control agents associated with Eichhornia crassipes in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, California. Biological Control, 111, 13-22.

Hopper, J. V., Pratt, P. D., Reddy, A. M., McCue, K. F., Rivas, S. O., & Grosholz, E. D. (2021). Abiotic and biotic influences on the performance of two biological control agents, Neochetina bruchi and N. eichhorniae, in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, California (USA). Biological Control, 153, 104495.

Hussner, A., I. Stiers, M.J.J.M. Verhofstad, E.S. Bakker, B.M.C. Grutters, J. Haury, J.L.C.H. van Valkenburg, G. Brundu, J. Newman, J.S. Clayton, L.W.J. Anderson, D. Hofstra. 2017. Management and control methods of invasive alien freshwater aquatic plants: A review. Aquatic Botany,136:112-137, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2016.08.002

Interior (U.S. Department of the Interior). 2016. Safeguarding America’s lands and waters from invasive species: A national framework for early detection and rapid response. Washington (DC): U.S. Dept of the Interior. 55 p. https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/National%20EDRR%20Framework.pdf

Johnston ME, Steel AE, Espe M, Sommer T, Klimley AP, Sandstrom P, Smith D. 2018. Survival of juvenile Chinook salmon in the Yolo Bypass and the lower Sacramento River, California. San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science 16(3). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8bq7t7rr

Khanna S, Conrad JL, Caudill J, Christman M, Darin G, Ellis D, Gilbert P, et al. 2018. Framework for aquatic vegetation monitoring in the Delta. Interagency Ecological Program Technical Report 92. https://cadwr.app.box.com/v/InteragencyEcologicalProgram/file/571038144141

Lay M, Khanna S, Rasmussen N, Ellis D, Zhou Z, Ustin SL. [2024?]. Species identification booklet for the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. https://cadwr.box.com/s/6bkv5lnsen4aght0ip9ao9xu4e5ol4jb

Mudge CR, Netherland MD. 2014. Response of giant bulrush, water hyacinth, and water lettuce to foliar herbicide applications. Journal of Aquatic Plant Management 52:75–80.

Reaser JK, Burgiel SW, Kirkey J, et al. 2020. The early detection of and rapid response (EDRR) to invasive species: a conceptual framework and federal capacities assessment. Biological Invasions 22:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-019-02156-w

Suisun Resource Conservation District. 2024. Suisun Marsh vegetation guidebook. Suisun City (CA): Suisun Resource Conservation District. 75 p. https://suisunrcd.org/2024-suisun-marsh-vegetation-guide-book/

Ta, J.; Anderson, L. W; Christman, M. A; Khanna, S.; Kratville, D.; Madsen, J. D, et al. (2017). Invasive Aquatic Vegetation Management in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta: Status and Recommendations. San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 15(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2017v15iss4art5 Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/828355w6

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), California Invasive Plant Council (Cal-IPC). 2018. Land manager’s guide to developing an invasive plant management plan. Cal-IPC Publication 2018-01. Sacramento (CA): USFWS, National Wildlife Refuge System, Pacific Southwest Region, Inventory and Monitoring Initiative; Berkeley (CA): California Invasive Plant Council. Available: https://www.cal-ipc.org and https://data.gov

Underwood GJC, Kromkamp J. 1999. Primary production by phytoplankton and microphytobenthos in estuaries. In: Nedwell DB, Raffaelli DG, editors. Advances in ecological research. Vol. 29. San Diego (CA): Academic Press. p. 93–153.

University of California Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program. 2025. What is IPM? https://ipm.ucanr.edu/what-is-ipm/#gsc.tab=0. Accessed 2025 Mar 19.

Sources for More Information

In addition to the resources listed within the Guide, the following provide helpful information:

- California Invasive Plant Council Best Management Practices Manuals and Guides

- Weed Management Areas

- University of California Weed Research and Information Center

- USDA Invasive Species and Pollinator Health Research Unit

- For more information, help locating resources mentioned in this guide, or to connect with a mentor who can provide advice on topics in this guide, please contact DIISCT at contact@deltaconservancy.ca.gov.

Here are some links to similar guides for other regions: